In 1564 the French attempted the first permanent settlement in what would later become the United States of America. They brought along with them a painter named Jacques le Moyne de Morgues. He was the first European artist to step foot in America and created the first artwork depicting Native Americans and their lifeways that any European would see. Thus his artwork and journals have left behind an invaluable record of Native American cultural traditions that have long since vanished.

In 1564 the French attempted the first permanent settlement in what would later become the United States of America. They brought along with them a painter named Jacques le Moyne de Morgues. He was the first European artist to step foot in America and created the first artwork depicting Native Americans and their lifeways that any European would see. Thus his artwork and journals have left behind an invaluable record of Native American cultural traditions that have long since vanished.

Painter in a Savage Land: the Strange Saga of the First European Artist in North America by Miles Harvey tells the story of le Moyne’s life from his time in La Florida, the Spanish name for all of the U.S., to his narrow escape, rescue and return to Europe. The story opens during the Atlantic crossing and establishes the world in which the painter currently lived and the current state of knowledge about the New World which was very little.

The story picks up steam as the colonists begin the construction of their fort and colony, called la Caroline, and begin their interactions with the local Native American tribe known as the Timucua. These interactions would begin friendly but over the course of the next few months the relationship would deteriorate putting the whole colonial efforts in jeopardy.

Yet the Timucua were not the only threat to the new French outpost. Spain claimed all of la Florida and thus saw the French interlopers as possible pirates, a threat to their treasure fleets that were shipping Mexican gold and silver back to Madrid. The Spanish fears were not misplaced for they would learn of this illegal French outpost after some of Fort Caroline‘s soldiers mutinied, stole some ships, and began pirate attacks on Spanish towns in the Caribbean. This mutiny, in turn, was the result of the failure of resupply ships to return to the French colony and save them from utter starvation.

Thus begins a race between the French resupply ships of Jean Ribault and the Spanish fleets of Pedro Menandez. But first, both mariners would have to escape the prisons that each had found themselves in, Ribault in London and Menendez in Seville.

The two fleets arrive in la Florida only weeks apart with the French arriving first. This should have resulted in victory for the French but a series of bad decisions would bring the French presence in the southeastern U.S. to an end. The first bad decision was Ribault, after learning about the arrival of the Spanish just south of the fort, decided to take all his best soldiers and ships and launch a full blown attack leaving Fort Caroline in the hands of sick and injured colonists. Oh, and did I mention it was the middle of hurricane season? I’m sure you can see where this is headed. Murphy’s Law comes into play and Ribault’s fleet gets swept away by a hurricane. The Spanish decided to attack Fort Caroline by land and so marched through days of rain and hurricane force winds. The second mistake the French made was focusing all their defensive efforts on the river side of the fort assuming the attack would come from this direction. It didn’t. And so the Spanish literally just walked into the fort from behind and slaughtered everyone in sight.

Le Moyne managed to escape, met a fellow escapee in the swamps surrounding the fort who attempted to convince Le Moyne to return with him to the fort to surrender. The logic was that it would be better to throw themselves at the mercy of the Spanish than starve to death in the swamps or be killed by wild animals or the natives. Le Moyne smartly declined and then watched from afar as his compatriot surrendered and was promptly hacked to death by the Spanish. Le Moyne eventually flagged down a passing British ship and was rescued and taken back to France where he would soon have to flee to London after Catholics in France decided to annihilate Protestants.

Meanwhile back in Florida the Spanish found the French castaways who had survived the hurricane after their ships grounded and broke apart. The Spanish promptly executed them all.

The story concludes with trying to trace down Le Moynes’ origins and birthplace with little success. This portion of the book is by far the least exciting but how could it not be?

The most curious part of the book was when the author noted the “errors” in Le Moyne’s paintings such as mountains in the background when no such geology exists in Florida. The author apparently accepted without question the mainstream contention that Fort Caroline was located on modern day St. John’s River in Jacksonville, Florida. Yet for the past 65 years not one shred of archaeological evidence has been found to support this contention. The author even writes about going along on one such archaeological dig with a professor from the University of North Florida to no avail. Had the author simply compared a modern map with the description of the location of the fort he would have realized that the St. Johns River simply doesn’t match.

For instance, the fort was said to be located on the River of May. Le Moyne notes,

“A long way from the place where our fort was built there are high mountains, called the Apalatci in the Indian language, where…three large streams rise and wash down silt in which a lot of gold, silver and copper is mixed. They put it in canoes and transport it down a great river, which we named the River of May and which flows to the sea.”

Clearly the St. Johns River does not flow from the Appalachian Mountains to the sea thus it can’t possibly be the River of May, the location of Fort Caroline. The closest such river would be the Altamaha River which lays some 85 miles north of Jacksonville, Florida at Darien, Georgia. In fact, the closest gold mines to Darien, Georgia lay just south of Athens, Georgia. Here lies the Apalachee River which flows into the Oconee River which flows into the Altamaha River. In other words, gold mines exist in the exact area where the French said they did. Thus, once one gets the proper location for the River of May, all the other “errors” simply disappear.

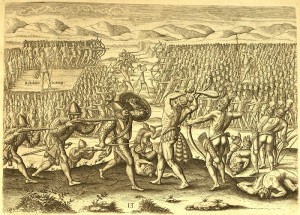

For instance, the aforementioned painting with hills or mountains in the background now becomes an accurate depiction of the location of the village of Potano where the French along with another tribe named the Utina had a great battle. According to Le Moyne they traveled up the River of May to reach Utina’s village. This village was said to be on the way to the lands of the Potano who were said to be mining gold near the mountains of Apalatci. All of these details only make sense when one realizes the River of May was the Altamaha River in Georgia not the St. Johns River in Florida. The Potano lived in the shadow of the Appalachian Mountains, not in the swamps of Florida, just as the painting depicts. (A tribe called the Potani did live near modern Ocala, Florida and were likely related to Georgia’s Potano.)

Additionally, years later the Spanish built a mission among the Utina called the Mission de Santa Isabell de Utinahica. This mission was located on the Altamaha River near either the Ohoopee or Oconee tributary. There was certainly never a mission to the Utina on the St. Johns River.

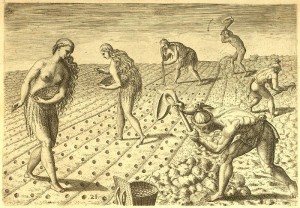

Yet time and time again the author declares the French accounts as fanciful and riddled with errors and accepts the mainstream academic accounts as gospel despite the fact that not one shred of physical evidence supports their claims. Another such glaring error comes when the author takes part in the failed archaeological dig with Dr. Ashley. The good professor claims another of Le Moyne’s paintings was a “total fabrication” because it shows Native Americans planting crops in rows and as any academic will tell you this simply was not a practice of Native Americans. Yet apparently Dr. Ashley was unaware of the archaeological evidence found at the Corn Field Mound at the Ocmulgee Mounds site, so-called because the mound was built over an old corn field that preserved precisely this type of row cropping. Coincidentally, this site also existed along a tributary of the Altamaha River in central Georgia, the exact area where Le Moyne claimed to have witnessed such practices.

Yet time and time again the author declares the French accounts as fanciful and riddled with errors and accepts the mainstream academic accounts as gospel despite the fact that not one shred of physical evidence supports their claims. Another such glaring error comes when the author takes part in the failed archaeological dig with Dr. Ashley. The good professor claims another of Le Moyne’s paintings was a “total fabrication” because it shows Native Americans planting crops in rows and as any academic will tell you this simply was not a practice of Native Americans. Yet apparently Dr. Ashley was unaware of the archaeological evidence found at the Corn Field Mound at the Ocmulgee Mounds site, so-called because the mound was built over an old corn field that preserved precisely this type of row cropping. Coincidentally, this site also existed along a tributary of the Altamaha River in central Georgia, the exact area where Le Moyne claimed to have witnessed such practices.

These agricultural rows unearthed at the Ocmulgee Mounds site in the 1930s are proof that Native Americans in Georgia did, in fact, use row cropping.

This bowing to the so-called “experts” instead of doing his own research is by far the most glaring error made throughout this book by the author. Luckily it doesn’t detract too much from the overall narrative and Painter in a Savage Land is still a worthy read about an incredibly interesting man, Jacques Le Moyne, and his adventures in America. These adventures, though, happened in Georgia not Florida and Le Moyne’s artwork and journals are not fabrications but instead accurate eyewitness accounts of the culture and lifeways of Georgia’s Native Americans. A book about Le Moyne should have made greater strides to unearth this truth in order to truly honor this great man.

[…] paintings claimed by academics is one showing Native Americans planting crops in rows. Academics assert that this was not a practice of Native Americans in Florida. Yet apparently these academics are […]

[…] ever been found proving the fort ever existed there or anywhere along that waterway. As I argued here and here, the overwhelming evidence supports that the fort was located somewhere on the Altamaha […]

[…] River near Darien, Georgia and not the St. Johns River near Jacksonville, Florida (as I argued here and here) then this presents a question: where was the original Fort St. Augustine? According to […]

[…] noted here and here, it is likely that the River of May was one-in-the-same as the Altamaha River in Georgia […]