Editor’s Note:

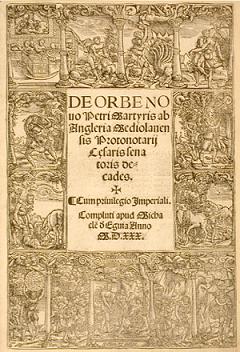

“The Testimony of Francisco de Chicora” published in Petyr Martyr’s De Orbe Novo in 1530 contains some of the first eyewitness accounts of Native Americans in the Southeastern United States and thus is an invaluable document. Amazingly, it not only includes Spanish eyewitness accounts of the lifeways and cultural practices of these Southeastern Indians but also includes information from a Native American informant as well, one Francisco de Chicora who had been captured years earlier in a raid by Spanish slavers who were the first to visit this area.

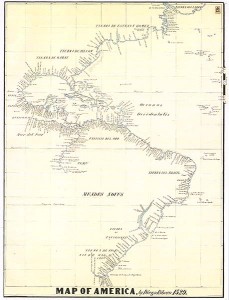

The information contained in the Testimony of Francisco de Chicora creates many new questions about America at the time of discovery. For instance, although Ayllon is credited by scholars with attempting the first European colony in the U.S. in 1526, his eyewitness accounts make it clear there was already a settlement of white people in South Carolina in a province called Duhare. In Gaelic du h’Eire translates as “Black Irish” and suggests the Irish created the first settlement in the U.S., not the Spanish.

Ayllon also witnessed what can only be described as fireworks in early America. How did fireworks arrive in America by 1536 when they didn’t arrive in Europe until the mid 1600s? These are just a few of the questions brought about by the Testimony of Francisco de Chicora.

Background Information (from Wikipedia):

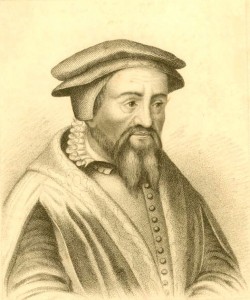

Francisco de Chicora was the baptismal name given to a Native American kidnapped in 1521, along with 70 others, from near the mouth of the Pee Dee River in South Carolina by Spanish explorer Francisco Gordillo and slave trader Pedro de Quexos, based in Santo Domingo and the first Europeans to reach the area. From analysis of the account by Peter Martyr, court chronicler, the ethnographer John R. Swanton believed that Chicora was from a Catawban group.

In Hispaniola, where he and the other captives were taken, Chicora learned Spanish, was baptized a Catholic, and worked for Lucas Vasquez de Ayllón, a colonial official. Most of the Catawba died within two years. Accompanying Ayllón to Spain, de Chicora met with the chronicler Peter Martyr and told him much about his people. Martyr combined this information with accounts by explorers and recorded it as the “Testimony of Francisco de Chicora,” published with his seventh “decade” in 1525. In 1526 Chicora accompanied Ayllón on a major expedition to North America with 600 colonists. After they struck land at the Santee River and the party went ashore, Chicora escaped and returned to his people.

Below is the English translation of Peter Martyr’s The Testimony of Francisco de Chicora.

The Testimony of Francisco de Chicora

Let us return to the country of these unfortunates, from which we have somewhat wandered. I believe this country is near that of Baccalaos, discovered by Cabot in the service of England some twenty-six years ago, or to the land of Bacchalais, of which I have already written at length. I shall now indicate their astronomical position, their religious rites, their products, and their customs.

These countries appear to be situated the same distance from the pole, and under the same parallel as Vandalia in Spain, commonly called Andalusia. The exploration of the country occupied but a few days. It extends a great distance in the same direction as the land where the Spaniards anchored. The first districts visited are called Chicorana and Duhare. The natives of Chicorana have a well-browned skin, like our sunburned peasants, and their hair is black. The men let their hair grow to the waist and the women wear theirs longer. Both sexes plait their hair and they are beardless; whether nature so created them or whether this is the result of some drug or whether they use a depilatory like the people of Temistitan, nobody can say. In any case they like to show a smooth skin.

I must cite another witness whose credit is not less among laymen than that of Dean Alvares amongst priests, namely the licenciate Lucas Vasquez Ayllon. He is a citizen of Toledo, member of the Royal Council of Hispaniola, and one of those at whose expense the two ships had been equipped.

Commissioned by the Council of Hispaniola to appear before the Royal India Council, he urgently asked that he might be permitted to again visit that country and found a colony. He brought with him a native of Chicorana as his servant. This man had been baptised under the Christian name of Francisco united to the surname of his native country, Chicorana. While Ayllon was engaged on his business here, I sometimes invited him and his servant Francisco Chicorana to my table. This Chicorana is not devoid of intelligence. He understands readily and has learned the Spanish tongue quite well. The letters of his companions which the licenciate Ayllon himself showed to me, and the curious information furnished me by Chicorana, will serve me for the remainder of my narrative.

Each may accept or reject my account as he chooses. Envy is a plague natural to the human race always seeking to depreciate and to search for weeds in another’s garden. even when it is perfectly clean. This pest afflicts the foolish or people devoid of literary culture, who live useless lives like cumberers of the earth.

Leaving the coast of Chicorana on one hand, the Spaniards landed in another country called Duhare. Ayllon says the natives are white men, and his testimony is confirmed by Francisco Chicorana. Their hair is brown and hangs to their heels. They are governed by a king of gigantic size, called Datha, whose wife is as large as himself. They have five children. In place of horses, the king is carried on the shoulders of strong young men, who run with him to the different places he wishes to visit.

At this point, I must confess, that the different accounts cause me to hesitate. The Dean and Ayllon do not agree; for what one asserts concerning these young men acting as horses, the other denies. The Dean said: “I have never spoken to anybody who has seen these horses,” to which Ayllon answered, “I have heard it told by many people,” while Francisco Chicorana, although he was present, was unable to settle this dispute. Could I act as arbitrator, I would say that, according to the investigations I have made, these people were too barbarous and uncivilised to have horses.

Another country near Duhare is called Xapida. Pearls are found there, and also a kind of stone resembHng pearls which is much prized by the Indians. In all these regions they visited, the Spaniards noticed herds of deer similar to our herds of cattle. These deer bring forth and nourish their young in the houses of the natives. During the daytime they wander freely through the woods in search of their food, and in the evening they come back to their little ones, who have been cared for, allowing themselves to be shut up in the courtyards and even to be milked, when they have suckled their fawns. The only milk the natives know is that of the does, from which they make cheese.They also keep a great variety of chickens, ducks, geese, and other similar fowls.

They eat maize-bread, similar to that of the islanders, but they do not know the yucca root, from which cassabi, the food of the nobles, is made. The maize grains are very like our Genoese millet, and in size are as large as our peas. The natives cultivate another cereal called xathi. This is believed to be millet but it is not certain, for very few Castilians know millet, as it is nowhere grown in Castile.

This country produces various kinds of potatoes, but of small varieties. Potatoes are edible roots, like our radishes, carrots, parsnips, and turnips. I have already given many particulars, in my first Decades, concerning these potatoes, yucca, and other foodstuffs.

The Spaniards speak of still other regions, Hatha, Xamiuiambe, and Tihe, all of which are beheved to be governed by the same king.’ In the last named the inhabitants wear a distinctive priestly costume, and they are regarded as priests and venerated as such by their neighbours. They cut their hair, leaving only two locks growing on their temples, which are bound under the chin. When the natives make war against their neighbours, according to the regrettable custom of mankind, these priests are invited by both sides to be present, not as actors but as witnesses of the conflict. When the battle is about to open, they circulate among the warriors who are seated or lying on the ground, and sprinkle them with the juice of certain herbs they have chewed with their teeth; just as our priests of the beginning of the Mass sprinkle the worshippers with a branch dipped in holy water. When this ceremony is finished, the opposing sides fall upon one another. While the battle rages, the priests are left in charge of the camp, and when it is finished they look after the wounded, making no distinction between friends and enemies, and busy themselves ‘in burying the dead.’

The inhabitants of this country do not eat human flesh; the prisoners of war are enslaved by the victors. The Spaniards have visited several regions of that vast country; they are called Arambe, Guacaia, Quohathe, Tazacca, and Tahor. The colour of the inhabitants is dark brown. None of them have any system of writing, but they preserve traditions of great antiquity in rhymes and chants. Dancing and physical exercises are held in honour, and they are passionately fond of ball games, in which they exhibit the greatest skill. The women know how to spin and sew. Although they are partially clothed with skins of wild beasts, they use cotton such as the Milanese call bombasio, and they make nets of the fibre of certain tough grasses just as hemp and flax are used for the same purposes in Europe.

There is another country called Inzignanin, whose inhabitants declare that, according to the tradition of their ancestors, there once arrived amongst them men with tails a metre long and as thick as a man’s arm. This tail was not movable like those of the quadrupeds, but formed one mass as we see is the case with fish and crocodiles, and was as hard as a bone. When these men wished to sit down, they had consequently to have a seat with an open bottom; and if there was none, they had to dig a hole more than a cubit deep to hold their tails and allow them to rest. Their fingers were as long as they were broad, and their skin was rough, almost scaly. They ate nothing but raw fish, and when the fish gave out they all perished, leaving no descendants. These fables and other similar nonsense have been handed down to the natives by their parents. Let us now notice their rites and ceremonies.

THE natives have no temples, but use the dwellings of their sovereigns as such. As a proof of this, we have said that a gigantic sovereign called Datha ruled in the province of Duhare, whose palace was built of stone, ^ while all the other houses were built of lumber covered with thatch or grasses. In the courtyard of this palace, the Spaniards found two idols as large as a three-year-old child, one male and one female. These idols are both called Inamahari, and had their residence in the palace.

Twice each year they are exhibited, the first time at the sowing season, when they are invoked to obtain a successful result for their labours. We will later speak of the harvest. Thanksgivings are offered to them if the crops are good; in the contrary case they are implored to show themselves more favotuable the following year. The idols are carried in procession amidst pomp, accompanied by the entire people. It will not be useless to describe this ceremony. On the eve of the festival the king has his bed made in the room where the idols stand, and sleeps in their presence. At daybreak the people assemble, and the king himself carries these idols, hugging them to his breast, to the top of his palace, where he exhibits them to the people. He and they are saluted with respect and fear by the people, who fall upon their knees or throw themselves on the ground with loud shouts. The king then descends and hangs the idols, draped in artistically worked cotton stuffs, upon the breasts of two venerable men, of authority. They are, moreover, adorned with feather mantles of various colours, and are thus carried escorted with hymns and songs into the country, while the girls and young men dance and leap.

Any one who stopped in his house or absented himself during the procession would be suspected of heresy; and not only the absent, but likewise any who took part in this ceremony carelessly and without observing the ritual. The men escort the idols during the day, while during the night the women watch over them, lavishing upon them demonstrations of joy and respect. The next day they are carried back to the palace with the same ceremonies with which they were taken out. If the sacrifice is accomplished with devotion and in conformity with the ritual, the Indians believe they will obtain rich crops, bodily health, peace, or if they are about to fight, victory, from these idols. Thick cakes, similar to those the ancients made from flour, are offered to them. The natives are convinced that their prayers for harvests will be heard, especially if the cakes are mixed with tears.

Another feast is celebrated every year when a roughly carved wooden statue is carried into the country and fixed upon a high pole planted in the groimd. This first pole is surrounded by other similar ones, upon which people hang gifts for the gods, each one according to his means. At nightfall the principal citizens divide these offerings among themselves just as the priests do with the cakes and other offerings given them by the women. Whoever offers the divinity the most valuable presents is the most honoured. Witnesses are present when the gifts are offered, who announce after the ceremony what every one has given, just as notaries might do in Europe. Each one is thus stimulated by a spirit of rivalry to outdo his neighbour.

From sunrise till evening the people dance round this statue, clapping their hands, and when nightfall has barely set in, the image and the pole on which it was fixed are carried away and thrown into the sea, if the country is on the coast, or into the river, if it is along a river’s banks. Nothing more is seen of it, and each year a new statue is made. The natives celebrate a third festival, during which, after exhuming a long-buried skeleton, they erect a black tent out in the country, leaving one end open so that the sky is visible; upon a blanket placed in the centre of the tent they then spread out the bones. Only women surround the tent, all of them weeping, and each of them offers such gifts as she can afford.

The following day the bones are carried to the tomb, and are henceforth considered sacred. As soon as they are buried, or everything is ready for their burial, the chief priest addresses the surrounding people from the summit of a mound, upon which he fulfils the functions of orator. Ordinarily he pronounces a eulogy on the deceased, or on the immortality of the soul, or the future life. He says that souls originally came from the icy regions of the north, where perpetual snow prevails. They therefore expiate their sins under the master of that region who is called Mateczunga, but they return to the southern regions where another great sovereign, Quescuga, governs. Quescuga is lame and is of a sweet and generous disposition. He surrounds the newly arrived souls with numberless attentions, and with him they enjoy a thousand delights,—young girls sing and dance, parents are reunited to children, and everything one formerly loved is enjoyed. The old grow young and everybody is of the same age, occupied only in giving himself up to joy and pleasure.

Such are the verbal traditions handed down to them from their ancestors. They are regarded as sacred and considered authentic. Whoever dared to believe differently would be ostracised. These natives also believe that we live under the vault of heaven; they do not suspect the existence of the antipodes. They think the sea has its gods, and believe quite as many foolish things about them as Greece, the friend of Hes, talked about Nereids and other marine gods,—Glaucus, Phorcus, and the rest of them.

When the priest has finished his speech, he inhales the smoke of certain herbs, puffing it in and out, pretending to thus purge and absolve the people from their sins. After this ceremony the natives return home, convinced that the inventions of this impostor not only soothe their spirits, but contribute to the health of their bodies.

Another fraud of the priests is as follows: when the chief is at death’s door and about to give up his soul, they send away all witnesses, and then surrounding his bed they perform some secret jugglery which makes him appear to vomit sparks and ashes. It looks like sparks jumping from a bright fire, or those sulphured papers which people throw into the air to amuse themselves. These sparks, rushing through the air and quickly disappearing, look like those leaping wild goats which people call shooting stars. The moment the dying man expires, a cloud of these sparks shoots up three cubits high, with a great noise and quickly vanishes. They hail this flame as the dead man’s soul, bidding it a last farewell and accompanying its flight with their wailings, tears, and funereal cries, absolutely convinced that it has taken its flight to heaven.

Lamenting and weeping they escort the body to the tomb. Widows are forbidden to marry again if their husband has died a natural death; but if he has been executed, they may remarry. The natives like their women to be chaste. They detest immodesty and are careful to put aside suspicious women. The lords have the right to have two women, but the common people have only one. The men engage in mechanical occupations, especially carpenter work and tanning skins of wild beasts; while the women busy themselves with distaff, spindle, and needle.*

Their year is divided into twelve moons. Justice is administered by magistrates, criminals and the guilty being severely punished, especially thieves. Their kings are of gigantic size, as we have already mentioned. All the provinces we have named pay them tributes and these tributes are paid in kind; for they are free from the pest of money, and trade is carried on by exchanging goods. They love games, especially tennis; they also like metal circles turned with movable rings, which they spin on a table, and they shoot arrows at a mark. They use torches and oil made from different fruits for illumination at night. They likewise have olive-trees. They invite one another to dinner. Their longevity is great and their old age is robust.

They easily cure fevers with the juice of plants, as they also do their wounds, unless the latter are mortal. They employ simples, of which they are acquainted with a great many. When any of them suffers from a bilious stomach, he drinks a draught composed of a common plant called Guihi, or eats the herb itself; after which he immediately vomits his bile and feels better. This is the only medicament they use, and they never consult doctors except experienced old women, or priests acquainted with the secret virtues of herbs. They have none of our delicacies, and as they have neither the perfumes of Araby nor fumigations nor foreign spices at their disposition, they content themselves with what their country produces and live happily in better health to a more robust old age. Various dishes and different foods are not required to satisfy their appetites, for they are contented with little.

It is quite laughable to hear how the people salute the lords and how the king responds, especially to his nobles. As a sign of respect, the one who salutes puts his hands to his nostrils and gives a bellow like a bull, after which he extends his hands towards the forehead and in front of the face. The king does not bother to return the salutes of his people, and responds to the nobles by half bending his head towards the left shoulder without saying anything.

I now come to a fact which will appear incredible to Your Excellency. You already know that the ruler of this region is a tyrant of gigantic size. How does it happen that only he and his wife have attained this extraordinary size ? No one of their subjects has explained this to me, but I have questioned the above mentioned licenciate Ayllon, a serious and responsible man, who had his information from those who had shared with him the cost of the expedition. I likewise questioned the servant Francisco, to whom the neighbours had spoken. Neither nature nor birth has given these princes the advantage of size as an hereditary gift; they have acquired it by artifice.

While they are still in their cradles and in charge of their nurses, experts in the matter are called, who by the application of certain herbs, soften their young bones. During a period of several days they rub the limbs of the child with these herbs, until the bones become as soft as wax. They then rapidly bend them in such wise that the infant is almost killed. Afterwards they feed the nurse on foods of a special virtue. The child is wrapped in warm covers, the nurse gives it her breast and revives it with her milk, thus gifted with strengthening properties. After some days of rest the lamentable task of stretching the bones is begim anew. Such is the explanation given by the servant Francisco Chicorana.

The Dean of La Concepcion, whom I have mentioned, received from the Indians stolen on the vessel that was saved explanations differing from those furnished to Ayllon and his associates. These explanations dealt with medicaments and other means used for increasing the size. There was no torturing of the bones, but a very stimulating diet composed of crushed herbs was used. This diet was given principally at the age of puberty, when it is nature’s tendency to develop, and sustenance is converted into flesh and bones. Certainly it is an extraordinary fact, but we must remember what is told about these herbs, and if their hidden virtues could be learned, I would willingly believe in their efficacy.

We understand that only the Kings are allowed to use them, for if any one else dared to taste them, or to obtain the recipe of this diet, he would be guilty of treason, for he would appear to wish to equal the king. It is considered, after a fashion, that the king should not be the size of everybody else, for he should look down upon and dominate those who approach him. Such is the story told to me, and I repeat it for what it is worth. Your Excellency may believe it or not.

I have already sufficiently described the ceremonies and customs of these natives. Let us now turn our attention to the study of nature. Bread and meat have been considered; let us devote our attention to trees.

THERE are in this country virgin forests of oak, pine, cypress, nut- and almond-trees, amongst the branches of which riot wild vines, whose white and black grapes are not used for wine-making, for the people manufacture their drinks from other fruits. There are likewise fig-trees and other kinds of spice-plants. The trees are improved by grafting, just as with us; though without cultivation they would continue in a wild state.

The natives cultivate gardens in which grows an abundance of vegetables, and they take an interest in growing their orchards. They even have trees in their gardens. One of these trees is called the corito, of which the fruit resembles a small melon in size and flavour. Another called guacomine bears fruit a little larger than a quince of a delicate and remarkable odour, and which is very wholesome; they plant and cultivate many other trees and plants, of which I shall not speak further, lest by telling everything at one breath I become monotonous.

Thanks to us, the licenciate and royal counsellor, Ayllon, succeeded in obtaining what he wanted. His Imperial Majesty accepted our advice, and we have sent him back to New vSpain, authorising him to build a fleet to carry him to those countries where he will found a colony. Associates will not fail him, for the entire Spanish nation is in fact so keen about novelties that people go eagerly anywhere they are called by a nod or a whistle, in the hope of bettering their condition, and are ready to sacrifice what they have for what they hope. All that has happened proves this. With what sentiments people so saddened by the robbery of their children and parents will receive them, time alone will show us.

Source: Anghiera, Pietro Martire d’, 1457-1526; Translated by MacNutt, Francis Augustus, 1863-1927. De orbe novo, the eight Decades of Peter Martyr d’Anghera. New York, London, G.P. Putnam’s Sons.