Does a newspaper account from 1817, rediscovered in 2010, reveal the location of the original Fort St. Augustine as being in Georgia not Florida?

As I noted in my article “Quest for Fort Caroline,” all of the written eyewitness accounts of the location of Fort Caroline suggested it was on the Altamaha River in Georgia and not the St. John’s River in Florida. This leaves one lingering mystery: where was the original Fort St. Augustine from which the Spanish launched their assault on this French fort? As I noted in my article “Fort St. Augustine Eyewitness Accounts,” the location of the original encampment from which the Spanish launched their assault was most likely on the Satilla River in southeastern Georgia and not the St. Mary’s River where academics have recently speculated.

The French claimed that the Spanish built their encampment by commandeering a Native American town named Seloy which they said was located on the River of Dolphins. The earliest map to show the location of this river was one from 1625 and it’s location and course were more consistent with the Satilla River than the St. Mary’s River. The French accounts also noted this Spanish encampment was just five or six leagues south of Fort Caroline which places it nearer the Satilla River than the St. Mary’s River. Additionally, the account by Spanish General Pedro Menendez who led the assault claimed it only took two days of marching to reach Fort Caroline from their encampment which is more consistent with a march starting from the north bank of the Satilla than from the St. Mary’s.

The Search Begins

With this information I decided to begin my search for possible locations of this original encampment along the Satilla River. Luckily I live in this very area, grew up here and my family has a history here going back to at least the 1800s. So my first suspicion was that the Indian town of Seloy (and thus the Spanish encampment) was at the site of a nearby Indian mound located in the Lampedocia area of northeastern Camden County. In fact, in a Google map I created on February 17, 2014 for my article “Quest for Fort Caroline” to illustrate the possible route of Menendez’s march from Seloy to Fort Caroline I located Seloy near the area where my father claimed this Indian Mound was situated.

View Menendez Georgia Route to Ft. Caroline in a larger map

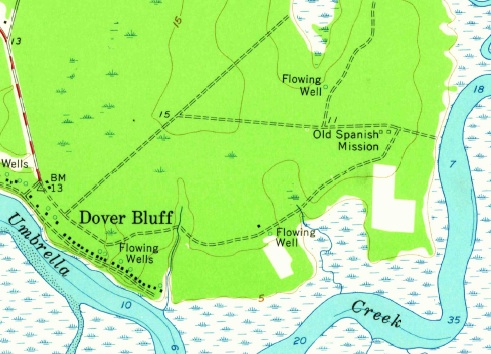

Back in 2004 I had tried to locate this mound again based on my uncle’s and father’s memories of its location. My father took me to two locations from where he claimed it could be seen but both locations were so heavily forested at that time we were unable to locate it. But I did notice that the local hunting club had labeled the access gate to this area “Indian Mound Rd” so I was convinced my father’s memories of its location were correct. I searched online for a topo map of the area and found one from the USGS dated to 1961 which clearly labeled a rectangular structure in this area as “Indian Mounds.” (These USGS surveyors must have been the “UGA students” my uncle remembered encountering at the mound in the early 60’s.) With this in mind I decided to look for this topo map again and found it. Below is a detail from the map showing the Indian Mounds.

Detail of the USGS 1961 Quadrangle of Dover Bluff, Georgia showing location of Indian Mounds near Sparkman Creek.

Since these were the only known Indian mounds in the vicinity and due to their location close to the mouth of the Satilla River, they would represent the best place to look for the Spanish fortified encampment but only if previous archaeological research had found that they dated to the right time period. So I decided to search again for any research done on these mounds. (Also on this same map just a little further east was a location labled “Old Spanish Mission” which I’ll discuss later.)

The Land of Lampedocia

Since the local area is known as Lampedocia (curiously pronounced “lamperdozer” in the thick southern accents of my father and uncle) after a 19th century plantation of that name, I decided to Google search for “Lampedocia Indian Mounds.” The first search result was a site report written in 2010 by Daniel T. Elliott from the LAMAR Institute entitled The Land of Lampedocia. Upon reaching the second page of the report I nearly fell out of my chair at what I was reading. Elliot had found a news report in the Dedham Gazette posted from “Lampedocia” dated to 1817 that stated the ruins of an old fort could be seen near Indian mounds in this area:

From the Savannah Republican:

Ancient Indian Fortification

‘Lampedocia, Little Satilla Neck, (Ga.) October 1, 1817. ‘In submitting for publication the underwritten true description of an ancient Indian fortification, I am warranted in the opinion of asserting, that it will be read with pleasure by many patrons of your widely circulated paper.

‘On the river Dover, a branch of the Great Satilla in this county, (Camden,) there is a remarkable fine bluff on the right bank, on which is situated a very ancient Indian fortification—I have viewed it particularly myself, as well as many of the most respectable gentlemen on this neck and vicinity, all of whom agree that it is one of the most ancient fortifications that was ever discovered in the United States. It has undoubtedly stood for centuries, from the decayed situation which it is now in—but, from the regularity and strength of the works, it is obvious that there must have been by far a more ingenious race of Aborigines than the present tribes, or those that were found at the first settlement of this country.

Each side of the fortification is about three hundred feet in length, and they are almost parallel with each other, and the walls, which are made of oyster shell and a kind of hard mould, are now more than ten feet high; but, no doubt, when first constructed were considerably higher: the top of which is now very even and broad, sufficiently so to admit of heavy cannon being placed thereon. The site on which it is built is remarkably exemplary of Indian ingenuity, being placed beside a beautiful spring rivulet, and notwithstanding which it has a very commanding position. At the northeast corner of the fort there is a small round outwork, the walls of which are as strong as any part, which admits of a narrow passage into the main fortification; and it also appears, that on this bluff was situated one of the largest towns of this ancient people, there being several large mounds of earth, thrown up on large masses of the dead, who are laid off in regular strata, one above the other; and there are also large pieces of earthen pots and other implements for domestic use’

This newspaper account features two requirements that the site of Seloy must possess: evidence of a large Native American town and evidence of a Spanish-style fortification.

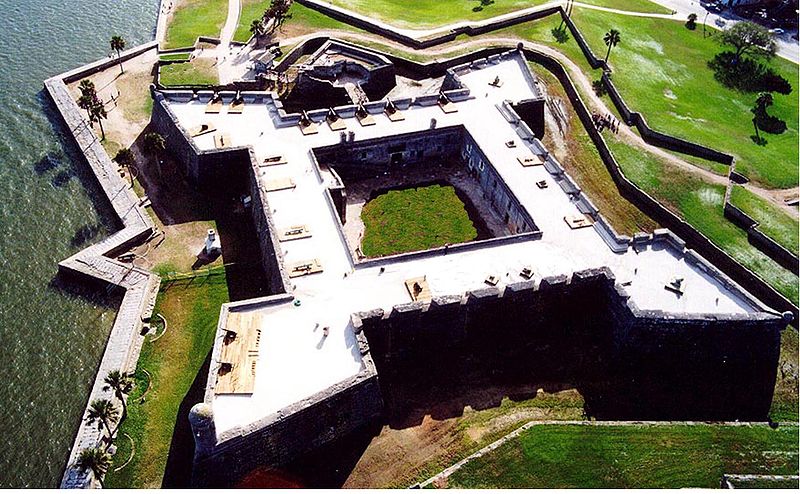

The description of the fort was very similar to the Castillo de San Marcos in modern-day St. Augustine (minus its bastions.) The Castillo is a square fort with walls 200 feet in length (not counting the bastions at each corner.) Thus the fort at Lampedocia was actually larger with walls 100 feet longer than the Castillo. Unlike the Castillo, whose walls were built from coquina stone, these walls were constructed from “oyster shell and a kind of hard mould” suggestive of tabby construction, a coastal building material similar to concrete. Tabby is thought to have been brought to the New World by the Spanish in the 1500s and Fort San Felipe on Parris Island, South Caroline dated to 1577 is believed to be the earliest Spanish use of tabby. Yet if the fort at Lampadocia was constructed in 1565 it would be one of the earliest if not the earliest structures constructed from tabby. The fact that the walls were wide enough to “admit…heavy cannon being placed thereon” is also similar to the construction of the Castillo at St. Augustine except at a smaller scale.

The Lampedocia fort also featured a “small round outwork…which admits of a narrow passage into the main fortification.” The Castillo has a similar feature protecting its sally port, or main entrance to the fort, but in a triangular shape not round. Known as a ravelin, this structure was meant to protect the entrance to the fort in the event of a land assault.

The newspaper account also mentioned “several large mounds of earth, thrown up on large masses of the dead, who are laid off in regular strata,” a clear reference to a Native American burial mound. Since the 1961 USGS topo map shows no other Indian mounds in the Dover Bluff area than the one labelled as such at Lampadocia and since the newspaper account was also posted from Lampedocia the odds are high that this USGS Indian Mounds location is one-in-the-same as the fort’s location in the 1817 newspaper account.

Of course, this “fort” description could also be a misinterpretation of a Native American shell ring. Shell rings, like those on nearby Sapelo Island, were doughnut-shaped mounds constructed from tons of oyster shells. But not all were ring-shaped. Some were U-shaped which could easily be misinterpreted as a square fort with an entrance where the gap existed. A shell mound in front of this gap could then be misinterpreted as a ravelin. Thus there are multiple ways to interpret this 1817 eyewitness account.

Ground Truthing

To say I was excited about the rediscovery of this 1817 newspaper account would be an understatement. Elliot’s “The Land of Lampedocia” report noted that the Indian Mound had been added to the Georgia Archaeological Site file in 1980 based solely on its appearance on the 1961 USGS topo map but that no site visit to confirm the mound had been made at that time. He also noted he had not made a site visit to confirm the mounds or fort cited in the 1817 newspaper account. Thus it looked like the job was up to me.

I first consulted a Google map of the area and noticed the entire area had been clear cut. This would make finding the mounds and the fort much easier than if it was still heavily forested. The weather was also cold and wet so no likelihood of snakes or bugs. So the next morning I drove to the area where my father had taken me in 2004 when we were unable to find the mound.

Across a large parcel of countless small pines, no taller than two feet in height, planted in perfect rows, I couldn’t believe my eyes. There appeared to be an enormous mound. So I got out and started walking towards it.

Along the way I noticed concentrations of oyster shell on the ground, a good sign of a Native American habitation site. As I got closer I realized the mound was enormous. Maybe not forty feet tall as my uncle remembered it but definitely over twenty feet tall. Its contours were now rounded due to decades of being plowed by the timber companies. In fact, the mound hadn’t even interrupted the perfectly straight rows of saplings. The plows simply continued plowing their rows directly over the mound and it was planted with the same evenly spaced pines as the rest of the parcel. When I finally reached the top of the mound I had a commanding view of the area. I could clearly see the locations across Sparkman Creek where my father had brought me in 2004. (See interactive 360 degree interactive panorama below taken from atop the mound. Notice my white truck on the road below the mound to geta sense of the mound’s height.)

The shape of the mound was somewhat unusual and not like those I’ve visited at other sites in Georgia. I couldn’t really make out a distinct form. It almost seemed L-shaped. For a moment I questioned if it wasn’t just an old debris pile that had been pushed up by bulldozers when they originally cleared the land for planting and now decades later simply looked like a mound of earth. I have similar debris piles on my own property from previous timber harvesting yet I’ve never seen one of these push-piles, as I call them, as large as the mound I was standing on. And the road that went by the base of the mound curved to follow the contours of the mound suggesting the mound was here before the road. All of this seemed to support that this was, indeed, the Indian Mound in question. Yet it wasn’t located where the topo map suggested it should be. Nor was it a neat, regular, rectangular shape as the topo map suggested. So I decided to climb down the hill and follow the road around to where the topo map suggested the “Indian Mounds” should be. This area hadn’t been clear cut and the pine forest was quite mature but luckily the undergrowth hadn’t fully leafed out yet. It was pretty easy to see straight through the trees and this revealed no Indian mounds. I decided to get out and walk around and did notice that in several places where there were old oak trees among the pines they appeared to be growing on small mounds several feet higher than the surrounding ground. Perhaps these were smaller Indian mounds that somehow survived the plows due to their oak hosts. (See interactive 360 degree panorama below.)

But there were certainly no ruins of a large fort. After walking around for awhile I thought about the site choices for most of the forts in this area. Fort Frederica on nearby St. Simons Island and Fort King George in Darien were both built on tidal creeks that came right up to the land allowing for small vessels to bring in supplies. At the present location there was several yards of marsh before one could reach the closest creek, Sparkman Creek. Who would want to walk across yards of muddy marsh to haul in supplies? But I did remember a nearby location where I remembered my father would take me fishing as a child where Dover Creek looped right up to the land. So I decided to drive to this area. (See interactive 360 degree panorama below.)

This would be an ideal location for a fort because you can literally step off the boat and onto dry land, no dock needed. But there isn’t much of a bluff at this location which was part of the description from the1817 newspaper account: “a remarkable fine bluff on the right bank, on which is situated a very ancient Indian fortification.” The closest bluffs are nearby Piney Bluff and Dover Bluff and both of these are developed with many homes. If a fort existed in either of those locations it would be well known by now.

View Seloy & Fort St. Augustine in a larger map

I had heard of tabby ruins on the ocean side of Dover Bluff that were once thought to be part of an old Spanish Mission. The USGS topo map actually listed these as well. Could these tabby ruins actually be ruins of a fort? Since these weren’t accessible I thought my best bet would be to return home and see if any research had ever been done on them.

After returning home I quickly found a 2011 Master’s Thesis entitled “TABBY: THE ENDURING BUILDING MATERIAL OF COASTAL GEORGIA” by Taylor Davis, a UGA Historic Preservation graduate student, devoted to tabby constructions in coastal Georgia. This paper included photos of the tabby ruins in Dover Bluff which turned out to be old slave cabins from a 19th century plantation. So this turned out to be a dead end.

Tabby slave cabins in the Dover Bluff area of Camden County, Georgia once mistakenly believed the ruins of an old Spanish mission. (c)2011, Davis Taylor

I also came across an abstract from archaeological research done at the River Marsh Landing development, a site due east of the Lampadocia Indian Mounds site. This research found both Native American and historic period artifacts in the area:

As a result of fieldwork, 374 forty-centimeter square shovel tests were excavated and one, previously recorded, archaeological site (9CM204) was further defined. The portions of site 9CM204 which lie within the current project tract consist of a variable density, multi-component site containing Woodland and Mississippian period prehistoric components, and historic materials dating to the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Historic materials were recovered from the plowzone, whereas prehistoric pottery was recovered from somewhat deeper subsurface contexts. The prehistoric component at 9CM204 appears to represents a short-term camp site utilized during several phases of prehistory. During its use, it was possibly tied to a residential base or village located elsewhere. The historic component of the site appears related to the use of the project tract during the nineteenth century as the outlying area of a plantation, and in the early twentieth century as a homestead. Based upon the absence of intact occupational strata, the lack of artifact concentrations as demonstrated through extensive delineation testing, the sparse nature of the artifact assemblage recovered thus far, the extensive disturbances this site has sustained, and the work already conducted, there does not appear to be a potential for future research at the investigated portions of site 9CM204 to generate significant data.

Since no remains of a large fort were found here even after archaeological investigations and the construction of multiple homes in the development, I think this rules out this location as a possible site of the fort.

With Dover Bluff, Piney Bluff and the River Marsh Landing sites ruled out, this leaves the Lampadocia Indian Mounds site as the only probable location for the ruins of the fort.

Encampment or Fort?

The ruins mentioned in the 1817 newspaper account are clearly those of a fort. But this leaves another mystery. The original Spanish accounts made a distinction between the original encampment and the fort which was to be built later. This means the encampment from which the Spanish launched their attack on Fort Caroline is also still lurking beneath the ground in this area as well.

View Seloy & Fort St. Augustine in a larger map

Both French and Spanish accounts noted they seized a Native American village once they reached shore and dug moats and trenches: “They went ashore and were well-received by the Indians, who gave them a very large house of a cacique which is on the riverbank. And then Captains Patiño and San Vicente, with strong industry and diligence, ordered a ditch and moat made around the house, with a rampart of earth and fagots…” Since Spanish infantry were trained in the construction of triangular shaped earthworks as temporary forts, could the triangular moat on Raccoon Key represent the location of the “large house of a cacique” which was converted into a fort?

If Raccoon Key is, indeed, the location of this original encampment it would also explain why Pedro Menendez stated, “When I go onshore we shall seek out a more suitable place to fortify ourselves in, as it is not fit where we are now. This we must do with all speed, before the enemy can attack us….” Raccoon Key is a small island which could easily be surrounded and bombarded by cannon-fire from French ships thus it is certainly not a suitable place for a long-term fort.

It would also explain a piece of information the local Indians gave Menendez. They told him he could reach Fort Caroline by water from his present location without going out to sea:

Many Indians were present, many of them chiefs, who showed themselves to be very friendly to us, and appear to us to be hostile to the French. They told us that, inside this harbor, and without going to sea, we could come to the river where the Frenchmen were, in front of their fort, by going up the river seven or eight leagues, which would be a very good thing, on account of being able to carry up the artillery and camp stores and cavalry, if we should wish to land near their fort, without being hindered by their island, although they have fortified it; moreover, we can go by land with horses and artillery. (Pedro Menendez, Letter II, September 11, 1565)

If one follows the tidal rivers from Raccoon Key up along the western side of Jekyll Island, across St. Simons Sound, and along the western side of St. Simons Island they will reach the south branch of the Altamaha River at Buttermilk Sound near Broughton Island without ever having to go out to sea. In 1776 William Bartram claimed to have seen the ruins of an ancient fortification on or near Broughton Island. In fact, there is a triangular-shaped area just west of Fridaycap Creek on Broughton Island which may represent the remains of triangular Fort Caroline. There are also large sand dunes to the southeast of this area which might represent the “mount” which French soldiers would climb to spot approaching ships and which Menendez claimed “about 50 or 60 persons escaped by swimming to the mountain” after he attacked the fort.

View Seloy & Fort St. Augustine in a larger map

Conclusions

There is certainly a mystery to be solved in the Lampadocia area of northeastern Camden County, Georgia. Either the newspaper account was a hoax or the remains of the original Fort St. Augustine are still lurking beneath the ground somewhere waiting to be unearthed by future archaeological investigations.

[…] Now it becomes clear that Menendez was also talking about the Altamaha River and not the St. John’s River as the location of Fort Caroline/San Matteo. But then he makes more confusing comments when he states that there are “three rivers and two ports” between “here” [St. Augustine] and Cape Canaveral. But there are definitely not “three rivers” and “two ports” between modern-day St. Augustine and Cape Canaveral. Matanzas Inlet near St. Augustine and Ponce Inlet near New Smyrna Beach are the only “rivers” or “ports” between these two locations. But there are, indeed, three rivers and two ports between the Satilla River in Woodbine, Georgia and Cape Canaveral: the St. Mary’s River, Nassau River and St. Johns River plus the two “ports” of St. Augustine Inlet and Ponce Inlet. (Apparently Matanzas Inlet wasn’t counted as a port. Even today no development has occurred on this inlet suggesting it doesn’t possess the qualities necessary for a port.) Once again, Menendez’s seemingly confused statements only make sense if Fort Caroline was on the Altamaha River and the original Fort St. Augustine was on the Satilla River. […]

[…] a St. John’s River in Jacksonville, Florida as has been believed for a past 150 years. Now new evidence published yesterday reveals that not usually was French Fort Caroline in southeastern Georgia […]