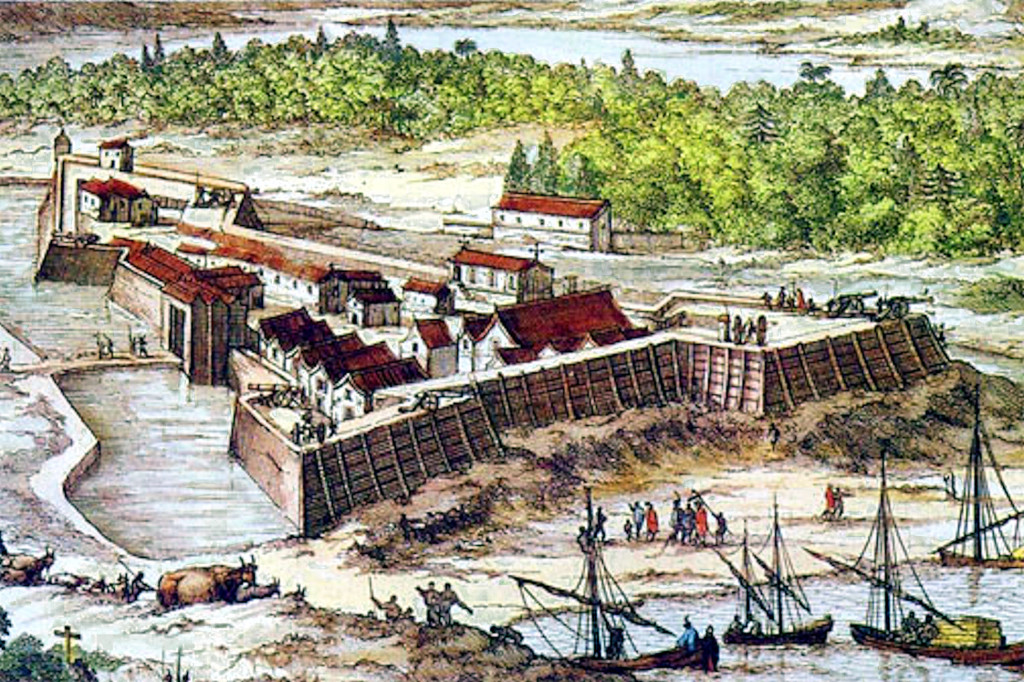

Evidence continues to accumulate that the site of Fort Caroline, the first European settlement in America, was actually in Darien, Georgia and not Jacksonville, Florida as has been long asserted. In fact, a 1/3 scale reproduction of the fort was constructed along the St. John’s River in Jacksonville despite the fact that no physical evidence has ever been found proving the fort ever existed there or anywhere along that waterway. As I argued here and here, the overwhelming evidence supports that the fort was located somewhere on the Altamaha River not the St. John’s River. Academics from Florida State University and the University of Florida now seem to agree. Read their press release below announcing their “discovery” of Fort Caroline on the Altamaha River (even though a similar claim was made here nearly two months earlier.) I’ve posted the entire press release below for archival purposes since the original press release from February 21, 2014 has already disappeared and replaced by the one below published on February 25, 2014.

Florida State University alumnus proposes location of country’s oldest fort during FSU conference

In an announcement that could rewrite the book on early colonization of the New World, two researchers have proposed new findings for the oldest fortified settlement in North America. Speaking Feb. 21 at an international conference at Florida State University, the pair proposed a new location in Southeast Georgia for Fort Caroline, a long-sought fort built by the French in 1564.

“This is the oldest fortified settlement in the United States,” said Florida State University alumnus and historian Fletcher Crowe. “This fort is older than St. Augustine, considered to be the oldest continuously inhabited city in America. It’s older than the Lost Colony of Virginia by 21 years; older than the 1607 fort of Jamestown by 45 years; and predates the landing of the Pilgrims in Massachusetts in 1620 by 56 years.”

The announcement was made at a large international conference held Feb. 20-21 at Florida State University in Tallahassee. The conference, hosted by FSU’s Winthrop-King Institute for Contemporary French and Francophone Studies and its Institute on Napoleon and the French Revolution, was “La Floride Française: Florida, France, and the Francophone World,” and commemorated the cultural relations between France and Florida since the 16th century. The conference drew scholars from across the globe.

Researchers have been searching for Fort Caroline for more than 150 years, Crowe said. The fort was long thought to be located east of downtown Jacksonville, Fla., on the south bank of the St. Johns River. The Fort Caroline National Memorial is located just east of Jacksonville’s Dames Point Bridge, which spans the river.

However, Crowe and his co-author, Anita Spring, a professor emeritus of anthropology at the University of Florida, say that the legendary fort is actually located on the Altamaha River in Southeast Georgia.

“This really is an important work of scholarship, and what a great honor it is for it to be announced at a conference organized by the Winthrop-King Institute,” said Martin Munro, a professor in FSU’s Department of Modern Languages and Linguistics and director of the Winthrop-King Institute. “It demonstrates the pre-eminence of the Institute and recognizes the work we do in promoting French and Francophone culture in Florida, the United States and internationally.”

Darrin McMahon, the Ben Weider Professor of History and a faculty member with Florida State’s Institute on Napoleon and the French Revolution, observed that Crowe and Spring’s finding — like the conference itself — highlights France’s longstanding presence in Florida and the Southeast.

“From the very beginning, down to the present day, French and Francophone peoples have played an important role in this part of the world,” McMahon said. “Our conference helped to draw attention to that fact.”

To conduct the research, Crowe, who received his Ph.D. in history from Florida State in 1973, flew to Paris and conducted research at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, the French equivalent of the U.S. Library of Congress, as well as at the P.K. Yonge Library of Florida History at the University of Florida, the Newberry Library in Chicago, and the Tampa Bay History Center. He found a number of 16th to 18th century maps that locate Fort Caroline. Some of the maps were in 16th-century French, others were in Latin and Spanish, and some were even in English.

Crowe was able to match French maps from the 16th to 18th centuries of what is today the southeastern coast of the United States with coastal charts of the United States published by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and with maps published by the U.S. Geological Survey.

One reason scholars claimed that Fort Caroline was located near Jacksonville is because they believed the local Indian tribes surrounding the fort spoke the Timucuan language, the Native American language of Northeast Florida.

However, “we have confirmation that the language (as recorded by the French in the 1650s) of the Native Americans living near the fort was Guale (pronounced “WAH-ley),” Spring said. “The Guale speakers lived in the Altamaha area, showing the fort was in Georgia.”

“The frustrating and often acrimonious quest to find the fort has become a great American mystery in archaeology,” Crowe noted.

In 1565, Spanish soldiers under Pedro Menéndez marched into Fort Caroline and slaughtered some 143 men and women who were living there at the time. The fort was taken over by the Spanish and renamed.

While studying in the Paris archives, Crowe found a 1685 map of French Florida that was accurately surveyed, and that allows known geographical points to be correlated with early maps of French Florida and contemporary maps and NOAA charts.

Using the known Global Positioning System (GPS) coordinates derived from an English map, Crowe was able to propose the location of dozens of Indian villages that up until now have eluded scholars and archaeologists.

“The next step is to do archaeological excavations to confirm the location as that of Fort Caroline,” Crowe said. In the excavation of Fort San Juan by Professor Christopher Rodning of Tulane University, the researchers found lead shot, nails, posts, beads and pottery that confirmed the date of authenticity of the find.

The Spanish fort that Rodning found had burned down, and researchers found a layer of black carbon about 1 meter beneath the surface, the residue of the fire. Crowe and Spring hope to find a similar layer of carbon at the Fort Caroline site, since the French fort burned twice, once in 1565 and again in 1568.

For 150 years, scholars have thought that “French Florida” meant mostly Northeast Florida, including Jacksonville, Lake City and Gainesville, spilling over to Southeast Georgia. The Crowe and Spring study would fundamentally redefine the term to include more of Southeast Georgia.

Crowe noted that “French Florida, by this new definition, forms a great oval extending from the Santee River of South Carolina, down to the St. Marys River, which serves today as the border between Georgia and Florida. French Florida extends from Darien on the coast, up to Milledgeville, east of Macon.”

Read the full press release here: http://artsandsciences.fsu.edu/In-the-News/Florida-State-University-alumnus-proposes-location-of-country-s-oldest-fort-during-FSU-conference

[…] Darien, Georgia then this encampment could be no further south than the Satilla River. Thus the recent assertion by two academics (who announced the “discovery” of Fort Caroline on the Altamaha River after it had […]