Does the discovery of the fevertree along the Altamaha River in Georgia by English naturalist William Bartram in 1775 help in the location of the lost French settlement of La Caroline?

In 1564 a young Frenchman living at the new settlement of La Caroline wrote a letter home describing the voyage and establishment of the fort. In this letter, published in Charles Bennett’s book Laudonniere & Fort Caroline, this Frenchman described the discovery of several important plant species near the fort:

“The fort is in the said River May, about six leagues up the river from the sea, which we will shortly have so well fortified as to have it defense-worthy, with very good conveniences and the water coming into the moat of the fort.

We even found a certain cinchona tree, which has dietary value, which is its least virtue…We have learned from the doctors that it sells very well in France and that it is well liked. Mr. de Laudonniere forbade our soldiers to send it aboard these ships, and only he would and did send some as a gift to the King and to the other Princes of France and to the Admiral, together with the gold which we had found there…” (1)

The fact that Laudonniere sent this plant along with gold to the King shows its high value to the French. But what is a cinchona tree and why is it so valuable? According to researchers, the cinchona tree is:

“native to the tropical Andean forests of western South America….A few species are used as medicinal plants, known as sources for quinine and other compounds…The medicinal properties of the cinchona tree were originally discovered by the Quechua peoples of Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador, and long cultivated by them as a muscle relaxant to abate shivering due to low body temperatures, and symptoms of malaria.” (2)

The fact that quinine, a remedy for malaria, is derived from the cinchona tree explains its value. But since the cinchona tree is native to the Andes, could it really be the plant the French found growing around Fort Caroline?

In October 1775 English naturalist William Bartram arrived at the Altamaha River in Georgia on his way to nearby Fort Barrington. While there he discovered two variety of shrubs new to him which he described in his book Travels:

In October 1775 English naturalist William Bartram arrived at the Altamaha River in Georgia on his way to nearby Fort Barrington. While there he discovered two variety of shrubs new to him which he described in his book Travels:

“I sat off early in the morning for the Indian trading-house, in the river St. Mary, and took the road up the N. E. side of the Alatamaha to Fort-Barrington. I passed through a well inhabited district, mostly rice plantations, on the waters of Cathead creek, a branch of the Alatamaha. On drawing near the fort, I was greatly delighted at the appearance of two new beautiful shrubs, in all their blooming graces. One of them appeared to be a species of Gordonia * , but the flowers are larger, and more fragrant than those of the Gordonia Lascanthus, and are sessile; the seed vessel is also very different. The other was equally distinguished for beauty and singularity; it grows twelve or fifteen feet high, the branches ascendant and opposite, and terminate with large panicles of pale blue tubular flowers, specked on the inside with crimson; but, what is singular, these panicles are ornamented with a number of ovate large bracteæ, as white, and like fine paper, their tops and verges stained with a rose red, which, at a little distance, has the appearance of clusters of roses, at the extremities of the limbs: the flowers are of the Cl. Pentan dria monogynia; the leaves are nearly ovate, pointed and petioled, standing opposite to one another on the branches.” (3)

Botonists have shown that the first of these shrubs was the Franklin tree (Franklinia Alatamaha) and the second was the Georgia bark or fevertree (Pinkneya pubens). It is this second tree, the fevertree, that provides the clue to the location of the lost Fort Caroline.

Botonists have noted the fevertree is

Botonists have noted the fevertree is

“a small tree of the southern United States closely resembling the cinchona or Peruvian bark, and belonging to the natural order Cinchonaceæ. It has pretty, large white flowers, with longitudinal stripes of rose-color. The wood is soft and unfit for use in the arts. The inner bark is extremely bitter, and is employed with success in intermittent fevers.” (4)

Thus the fevertree is clearly the “cinchona tree” that the young Frenchman referred to as living near Fort Caroline. But where does this plant grow?

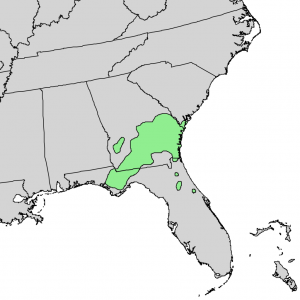

According to a map produced by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (5), the plant primarily grows in Georgia along the coast and inland in a narrow band reaching to the Gulf of Mexico in northwest Florida. According to this map there also appear to be three small populations in inland Florida.

An 1885 article in The American Journal of Pharmacy notes:

“Michaux discovered this plant in 1791, along the banks of the St. Mary’s River, Florida, and described it as follows: It grows in bogs along the banks of streams from Florida to South Carolina, near the coast…The plant is closely related to the cinchonae, and is one of the many that have been proposed as a substitute for Peruvian bark. From reports of physicians living in States where it grows, it appears to have decided anti-periodic properties, though slower in its action than cinchona bark. The genus was named in honor of Gen. Charles Pinckney, of South Carolina.” (6)

Except for this 1791 account of it growing at the St. Mary’s River, the border between Georgia and Florida, it does not appear to grow along the northeast coast of Florida nor along the St. Johns River. This would seem to preclude these locations as being possible sites of Fort Caroline.

Unless the range of this plant has changed in modern times, it would seem this is one more piece of evidence supporting the hypothesis that Fort Caroline was located on either the Altamaha River or St. Mary’s River and not the St. John’s River.

Sources

1. Bennett, Charles E. Laudonniere & Fort Caroline: History and Documents. (p.68)

2. “Cinchona.” Wikipedia.org. Accessed online 3 January 2017 at <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cinchona>.

3. Bartram, William. Travels.

4. “Georgia Bark.” Collier’s New Encyclopedia. Accessed online 3 January 2017 at <https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Collier%27s_New_Encyclopedia_(1921)/Georgia_Bark>.

5. “Pinckneya pubens.” Digital Representations of Tree Species Range Maps from “Atlas of United States Trees” by Elbert L. Little, Jr. (and other publications). USGS.gov. Accessed 3 January 2017 at <https://gec.cr.usgs.gov/data/little/pincpube.pdf>.

6. “Pinckneya pubens, Michaux. (Georgia Bark.)” The American Journal of Pharmacy. April 1885. Accessed online 3 January 2017 at <http://www.henriettes-herb.com/eclectic/journals/ajp/ajp1885/04-pinckneya.html>.