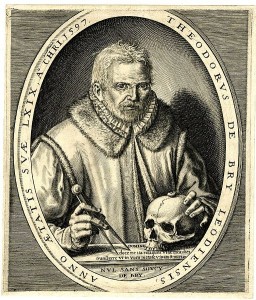

Theodorus de Bry (1528 – 27 March 1598) was an engraver, goldsmith and editor who traveled around Europe, starting from the city of Liège (where he was born and grew up), then to Strasbourg, Antwerp, London and Frankfurt, where he settled.

Theodorus de Bry (1528 – 27 March 1598) was an engraver, goldsmith and editor who traveled around Europe, starting from the city of Liège (where he was born and grew up), then to Strasbourg, Antwerp, London and Frankfurt, where he settled.

Theodorus de Bry created a large number of engraved illustrations for his books. Most of his books were based on first-hand observations by explorers, even if De Bry himself, acting as a recorder of information, never visited the Americas. To modern eyes, many of the illustrations seem formal but detailed.

Life

Theodorus de Bry was born in 1528 in Liege, east of today’s (2008) Belgium, to a family who had escaped the destruction of the city of Dinant in 1466 by the Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Good and his son Charles the Bold. As a man he trained under his grandfather, Thiry de Bry senior (? – 1528), and under his father, Thiry de Bry junior (1495–1590), who were jewelers and engravers, engraving copper plates. The art of copper plate engraving was the technology of that time required for printing images and drawings as part of books. In 1524, Thiry de Bry junior married Catherine le Blavier, daughter of Conrad le Blavier de Jemeppe. Their son, Theodorus de Bry, also became a jeweler, engraver and book editor and publisher, famous most notably for his depictions of early European expeditions to the Americas.

Around 1570, Theodorus de Bry, a protestant, fled religious persecution south to Strasbourg, along the west bank of the Rhine. In 1577, he moved to Antwerp in the Duchy of Brabant, which was part of the Spanish Netherlands or Southern Netherlands and Low Countries of that time (16th Century), where he further developed and used his skills as a copper engraver. Between 1585 and 1588 he lived in London, where he met the geographer Richard Hakluyt and began to collect stories and illustrations of various European explorations, most notably from Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues.

In 1588, Theodorus and his family moved permanently to Frankfurt-am-Main, where he became citizen and began to plan his first publications. The most famous one is known as Les Grands Voyages, i.e., “The Great Travels”, or “The Discovery of America”. He also published the largely identical “India Orientalis-series”, as well as many other illustrated works on a wide range of subjects. His books were published in Latin, and were also translated into German, English and French to reach a wider reading public.

In 1590 Theodorus de Bry and his sons published a new, illustrated edition of Thomas Harriot’s A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia about the first English settlements in North America (in modern-day North Carolina). His illustrations were based on the watercolor paintings of colonist John White.[2] The book sold well and the next year de Bry published a new one about the first French attempts to colonize Florida. It had accounts of Jean Ribault and René de Laudonnière about the attempt to found the French colony of Fort Caroline and 43 illustrations based on paintings of Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues, one of the few survivors of Fort Caroline. Jacques de Moyne had planned to publish his account of his expeditions but died 1587. According to de Bry’s account, he had bought de Moyne’s paintings from his widow in London and used them as a basis for the engravings.

He and his son John-Theodore (1560–1623) made adjustments to both the texts and the illustrations of the original accounts, on the one hand in function of his own understanding of Le Moyne’s paintings, and, most importantly, to please potential buyers. The Latin and German editions varied markedly, in accordance with the differences in estimated readership. Amerindians look like Mediterranean Europeans and illustrations mix different tribal customs and artifacts. In addition to day-to-day life of the American natives, Theodore de Bry even included a few depictions of cannibalism. All in all, the vast amount of these illustrations and texts influenced the European perception of the New World, Africa, and Asia.

The verisimilitude of many of de Bry’s illustrations is questionable; not least because he never crossed the Atlantic. Modern archaeologists and historians have noticed a number of misunderstandings and mistakes. Florida archaeologist Jerald T. Milanich has expressed doubts that Theodorus de Bry really used le Moyne’s original paintings, because, according to his sources, most of le Moyne’s surviving illustrations are botanical. But perhaps that these botanical illustrations were not bought by T. de Bry. As the botanical part was left in England, separated from the other illustrations which T. de Bry took with him, when going back to his family at Frankfurt, Germany, that may explain this apparent discrepancy.

Among other works he engraved a set of twelve plates illustrating the Procession of the Knights of the Garter in 1587, and a set of thirty-four plates illustrating the Procession at the Obsequies of Sir Philip Sidney; plates for Thomas Harriot’s Brief and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia (Frankfurt, 1590); the plates for the six volumes of Jean-Jacques Boissard’s Romanae Urbis Topogrephia et Antiquitates (1597–1602); and, with Boissard, a series of 100 portraits and biographies of humanists and protestants entitled Icones Virorum Illustrium (1597–1599).

De Bry had been assisted by his two sons, Johann Theodor de Bry (1561–1623) and Johann Israel de Bry (1565–1609) who after their father’s death in Frankfurt-am-Main on 27 March 1598 carried on the Collectiones (expanded to voyages in Asia, reaching 30 volumes) and the illustration of Boissard’s work, and also added to the Icones and other significant publications, like Robert Fludd’s works on the microcosm and macrocosm.

His work and engravings can today be consulted at many museums around the world, including Liège, his birthplace, and at Brussels in Belgium. In France, they are housed at the Library of the Marine Historical Service, at the “Château de Vincennes”, on the outskirt of Paris. In the USA, there are copies at the Public Library of New York, at the University of California at Los Angeles, and elsewhere. At Argentina is possible to find copies at Museo Maritimo de Ushuaia, at Tierra del Fuego and at the Navy Department of Historic Studies, at Buenos Aires.

Last but not least, his engravings, which were in black and white have recently been put into colors, which adds a new dimension to his masterpieces [Bouyer M. & Duviols J.-P., 1992]

(courtesy Wikipedia)

[…] Theodor de Bry | TheNewWorld.us […]